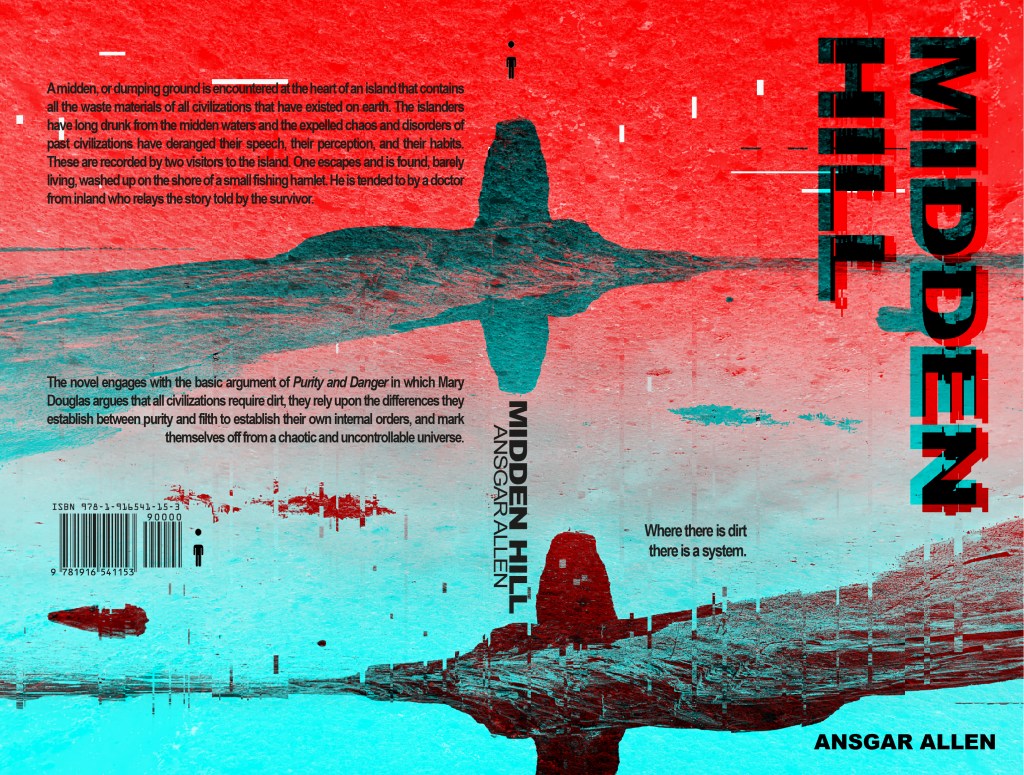

Midden Hill

2025, Schism2.

Available in Paperback via retailers including Barnes & Noble, Blackwell’s & Amazon (US UK DE FR ES IT NL PL SE JP CA AU).

REVIEWS

Matthew Kinlin, XRAY Lit Mag, 31 Oct 2025; David Vichnar, Erratum Reviews, 26 Sept 2025.

“Unlike straightforward allegory or conventional philosophical treatise, Midden Hill inhabits the zone between narrative, parable, and fragmentary essay. The text stages the experience of thinking as an ordeal: not a progressive journey towards enlightenment but a continual brushing up against obscurity, exhaustion, and the violent enclosures of institutional knowledge. Allen’s narrative centres on an island composed entirely of civilisation’s waste: cultural artifacts, detritus, language fragments, archival trash. Visitors to the island report distorted speech and perception, as if society’s detritus infects cognition… Here, Allen rewrites classical metaphors of knowledge as nourishment (Plato’s dietetics of the soul, Bacon’s digestion of experience) into grotesque corporeal parody. In so doing he provides an arch-archival metaphor: the mind consumes and digests exterior chaos, but only extrudes intellectual sediment… Allen’s prose refuses the consolations of philosophical clarity, but instead makes palpable the exhaustion, violence, and futility at the heart of the pedagogical project, positioning fiction itself as the only form capable of enacting this critique from within.” — David Vichnar

“‘Our assignment was this. To record what the islanders did and what they said.’ Ansgar Allen’s Midden Hill offers the mind-bending dictation of a patient to his doctor about his time spent on an island with a midden, an incredible refuse hill, in the centre. Reminiscent of J.G. Ballard’s Concrete Island, Allen offers a confounding examination of civilisation and its discontents. The midden on the island is described as the dumping ground for the entire planet, made up of ‘everything every culture has expelled from itself.’ An abject zone that ‘contains all defilements, all forbidden objects, all expulsions.’ The book opens with a quote from Mary Douglas, an anthropologist who writes about purity and uncleanliness, and the rituals of purification central to modern cultures. There is a system to man’s filth. His safety is predicated on his daily attempts to expel waste and form himself in opposition to this. The island seems to place all of that in jeopardy. It carries perverse rituals of its own, mirrored in the vortical writing of Allen, as his visitors navigate this land of symbolic chaos: the burning and inhalation of a mysterious weed, the appalling significance of a peeled egg. In a way, the book captures something of Kafka’s The Castle; an outsider caught in an alien system, tunnels and tunnels of endless rot.” — Matthew Kinlin

DESCRIPTION

A midden, or dumping ground is encountered at the heart of an island that contains all the waste materials of all civilizations that have existed on earth. The islanders have long drunk from the midden waters and the expelled chaos and disorders of past civilizations have deranged their speech, their perception, and their habits. These are recorded by two visitors to the island. One escapes and is found, barely living, washed up on the shore of a small fishing hamlet. He is tended to by a doctor from inland who relays the story told by the survivor.

The novel engages with the basic argument of Purity and Danger in which Mary Douglas argues that all civilizations require dirt, they rely upon the differences they establish between purity and filth to establish their own internal orders, and mark themselves off from a chaotic and uncontrollable universe.

EXTRACT

“Think of the mind as a vessel that takes in its exterior. It must surely liquify what it incorporates, boil it down, and then extrude only the finest scum of that concoction, otherwise the vessel would fill with a few short glances at the world it sees. Room must be made as well—if we think of the mind as a vessel—to allow the incorporation of forces. We may think of speech as a mechanism of removal, of the mouth as the first orifice of expulsion, and of the necessity of talking as the necessity of making room in the mind for its growth within the confines of the head. The skull cavity is the ultimate limit that halts growth and maintains humanity in its comparative ignorance. Trepanning—the boring of a hole into the head—has to be the most audacious of refusals of the limits of the mind. False testimony ascribes the origins of trepanning to the expelling of spirits, the treatment of madness, or to the evacuation of inner pressure. The origins of trepanning are poorly understood indeed. Few realise that the boring of skulls originated as a practice to rival the great philosophic inquisitors—the pioneers of philosophic thought before its systematisation—who themselves sought to take thought and perception to its extremities but had, or only employed to that purpose, their means of intellection for tools, a reflective pose that will never discover anything of the nature of existence from the serene aspect. Trepanation produced the first true philosophers of experience. The expulsion of spirits and the alleviation of madness were, if they were stated as reasons, mere stand-ins for a more serious purpose, a purpose which could not be articulated to the satisfaction of their non-trepanning peers. Perhaps too few survived even as the construction of the trephine, the circular auger, was perfected. But as they sat and had themselves bored out, they perceived levels of stimulus that the mind will not usually admit and saw the energies of the vastness outside of them with unfiltered clarity.”