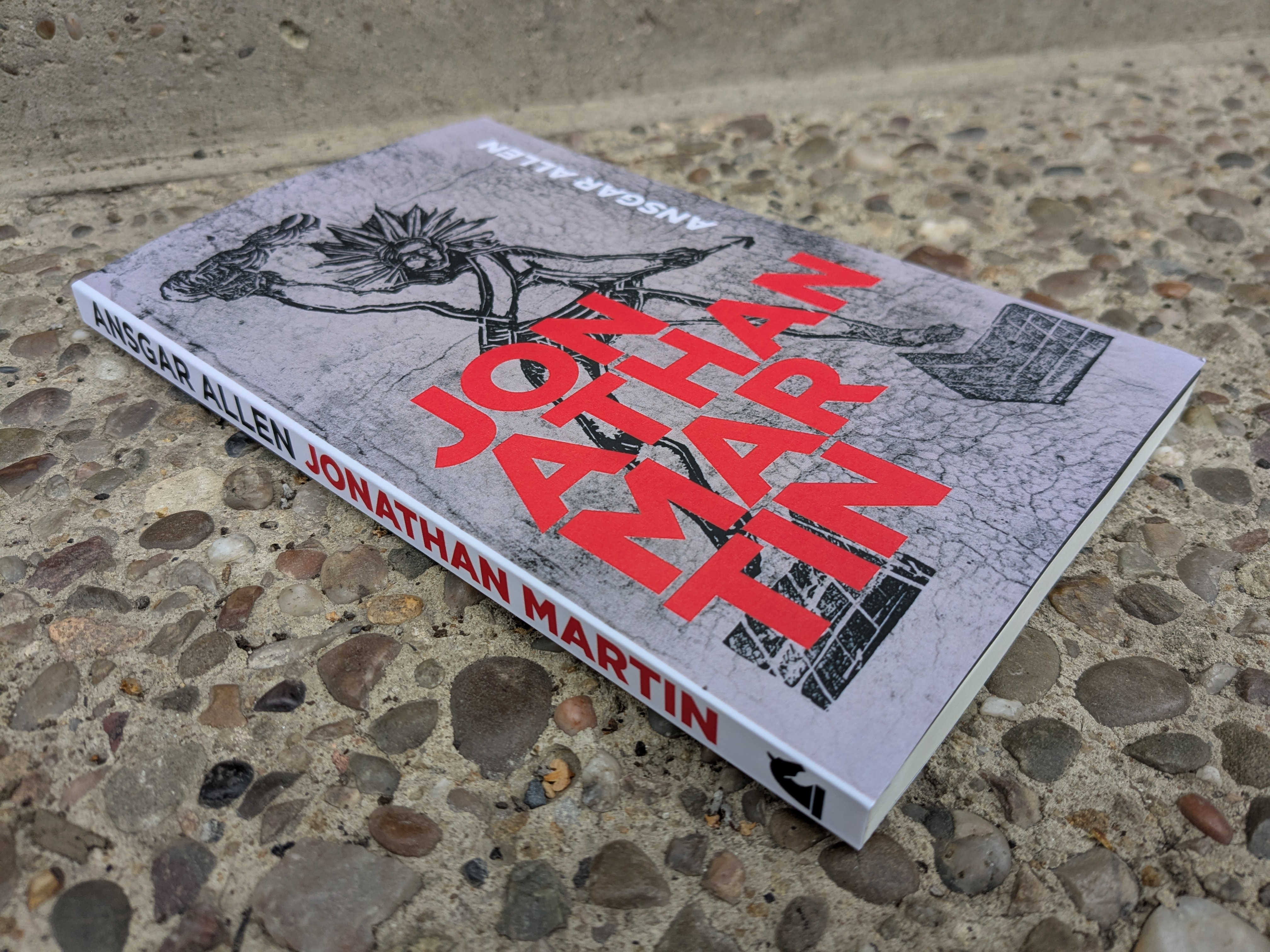

Jonathan Martin

2025, Equus Press. [excerpts Ch1, Ch3]

Available in Paperback via retailers including Lulu, Barnes&Noble, Blackwells & Amazon (UK US AU DE CS FR NL PL JP CA)

This novel, or book of fragments, tells the life of Jonathan Martin (1782-1838), a self-proclaimed prophet and certified lunatic, who set fire to York Minster in 1829, and was committed to Bedlam that same year.

“Ansgar Allen’s new novel tableaus a life in fragments, exhibiting—by way of public dissection—a relentlessly detached and digressive sequence of blunt, dry, unflinching incisions into the heart of bleakness. Undeniably blackly comic, Jonathan Martin metafictionally nods to Tristram Shandy and B.S. Johnson, mocking the absurdity of the one-POV historic novel and our own needs for the impossible, mythological “truth.””—Vik Shirley

“This book is an act of negation, it tells us what literature is by telling us what it is not, what it can’t do and what it won’t. It is appositely negative-theological, it is also an act of arson of a sort.”—Steve Hanson

“Jonathan Martin does not offer a linear tale of madness but a polyphonic reconstruction, where voices collide and history itself burns. Allen’s prose inhabits Martin’s broken language and visionary fury, producing a narrative that is as unsettling as it is hypnotic. At once historical fiction, philosophical meditation, and radical experiment, Jonathan Martin is a novel of fire and prophecy, of derangement and divine vengeance, that confronts the reader with the instability of reason and the dangerous allure of belief.”—David Vichnar

REVIEWS

David Vichnar, Erratum Reviews, 26 Sept 2025; Steve Hanson, Manchester Review of Books, 17 Sept 2025.

DESCRIPTION (BY EQUUS)

In his new novel Jonathan Martin, Ansgar Allen resurrects the incendiary life of the 19th-century outsider who, in 1829, set fire to York Minster. Martin’s life — at once prophetic, deranged, and tragically emblematic of his age — becomes the ground for Allen’s boldest experiment in historical fiction to date. Blending archival fragments, self-published pamphlets, trial records, and fictionalised reconstructions, Jonathan Martin asks: was Martin a prophet or a lunatic, an arsonist or a visionary? Allen’s prose, at turns Joycean, Woolfian, and Beckettian, inhabits Martin’s fractured language and his millenarian visions, bringing to life a world teetering between religious ecstasy, madness, and political upheaval. Structured in fragments that echo Martin’s broken language and visions, the novel interlaces biography, dream, trial record, and philosophical meditation. Martin’s story collides with those of his siblings — William the “Philosophical Conqueror of All Nations,” John the Artist, Richard the Poet-Quartermaster — each of whom embodies another skewed path of enlightenment or ruin. At the centre stands Jonathan: incendiary, prophet, lunatic. A powerful meditation on authorial voice, writing as prophecy, and the boundaries between sanity and inspiration, Jonathan Martin continues Allen’s exploration of education, deviance, and social order. It is a work of fiction that refuses to perpetuate the illusion of coherence, confronting the reader instead with the broken totality of a life lived on the edge of destruction.

LAUNCH VIDEO

FROM INSIDE THE BOOK

JONATHAN MARTIN & NECROMODERNISM (BY EQUUS)

Jonathan Martin presents itself less as a “life novel” than as a necromantic reanimation of biography as ruin, disjunction, and haunted fragment. “On 27 May 1838, Jonathan Martin lay down and died … That evening, another lunatic would take his place, and the room in which he lived would be occupied by another man’s thoughts.” This opening gesture already signals a necromodernist logic of succession, recurrence, and the absorption of subjectivity into haunted space. Allen does not begin with origin or ascent; he begins with death, as implosion rather than birth, insisting that a life as biography is always parasitic upon its own ending. The novel is structured in fragments — archival scraps, trial documents, self-published pamphlet inserts, delirious registers — weaving together dream, ecclesiastical fury, and claustrophobic psychosis. Hanson describes the book as “an act of negation … it tells us what literature is by telling us what it is not.” This refusal of teleology, this negative theology of biography, is quintessentially necromodern: identity survives (if it survives) not by coherence but by decomposition, margin, and interruption. Within the Equus necromodernist canon, Jonathan Martin marks a bold pivot: it is no longer city-archive or glitch event, but biographical necropolis. The life of Jonathan—prophet, arsonist, inmate—is neither fully recoverable nor fully imagined: Allen treats historical source as spectral matter, medium to be excavated rather than exhumed. He rewrites the conventions of historical fiction, pushing biography toward ruin, exposing the hollowness of coherence and claiming the haunted residue of a life lived on the margins of reason and order.

GALLERY OF IMAGES

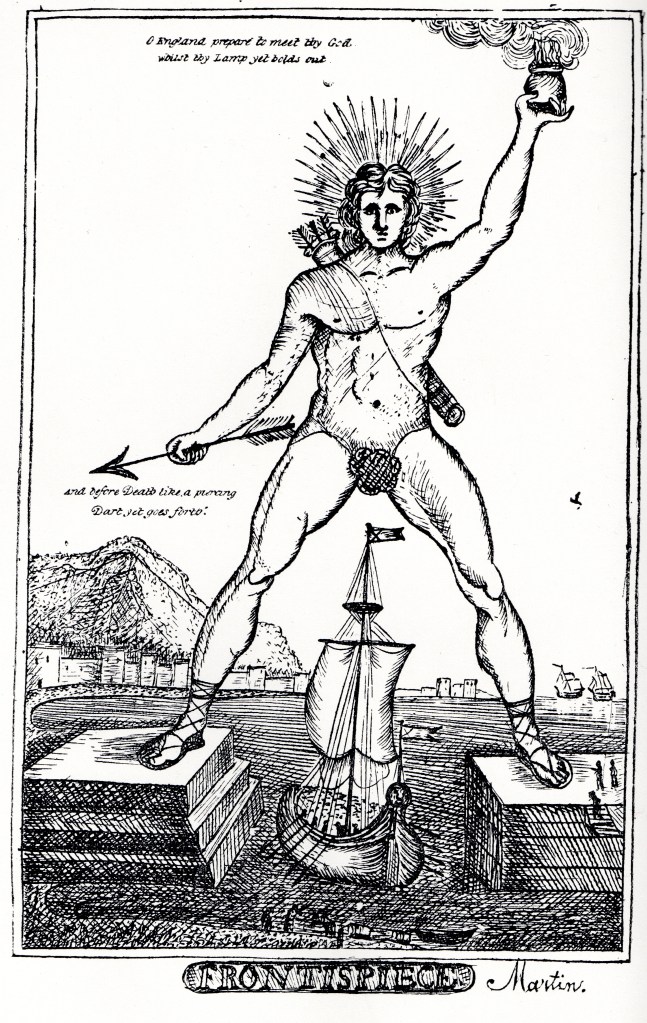

The Son of Bonaparte, from The Life of Jonathan Martin, 2nd Edition, 1826

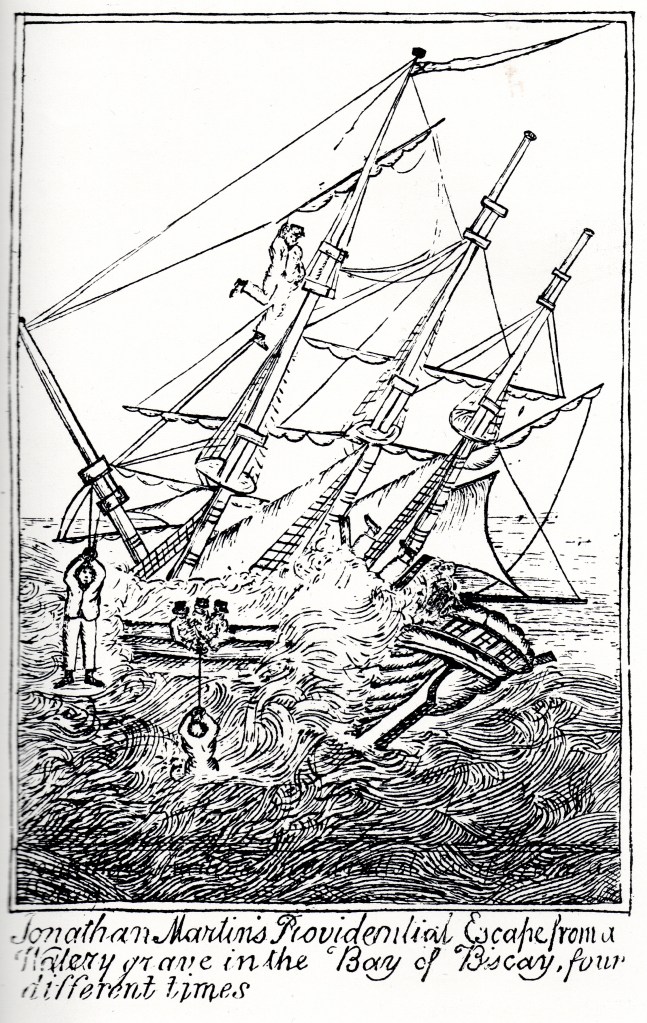

Jonathan Martin’s Providential Escape from a Watery Grave, from The Life of Jonathan Martin, 1826

THE FIRE AND AFTERMATH

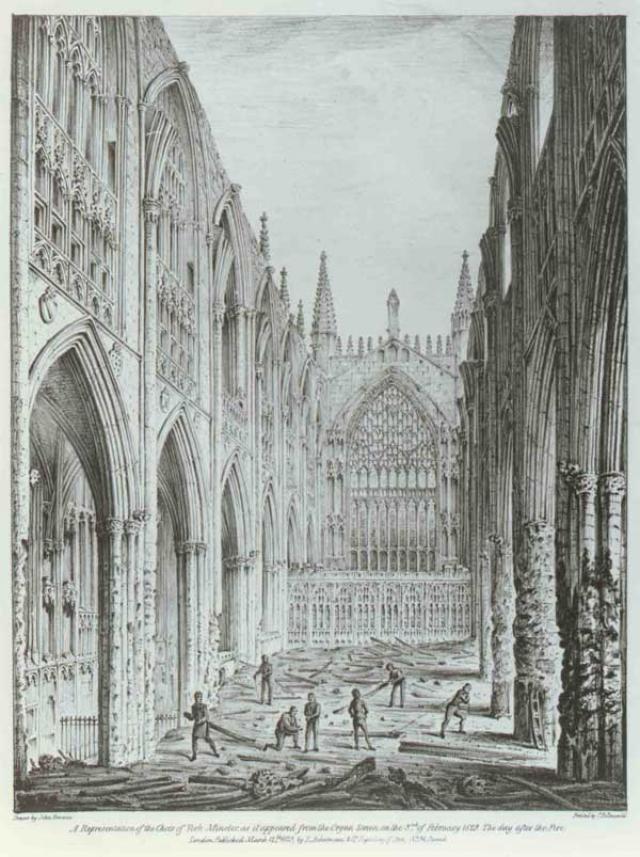

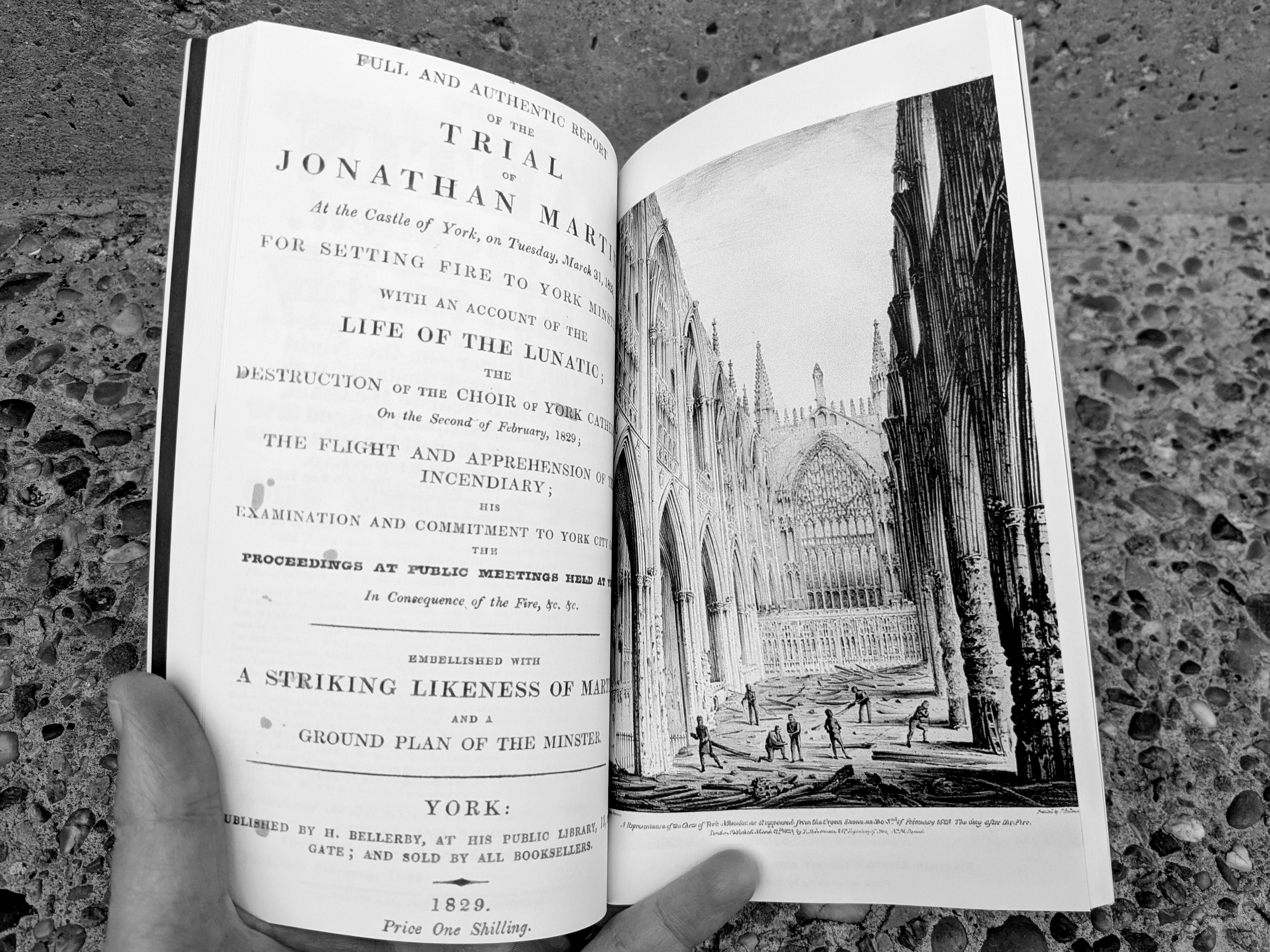

Sketch of York Minster as on Monday 2 February 1829, from a pen-and-ink sketch by an eyewitness, reproduced in Thomas Balston The Life of Jonathan Martin, 1945

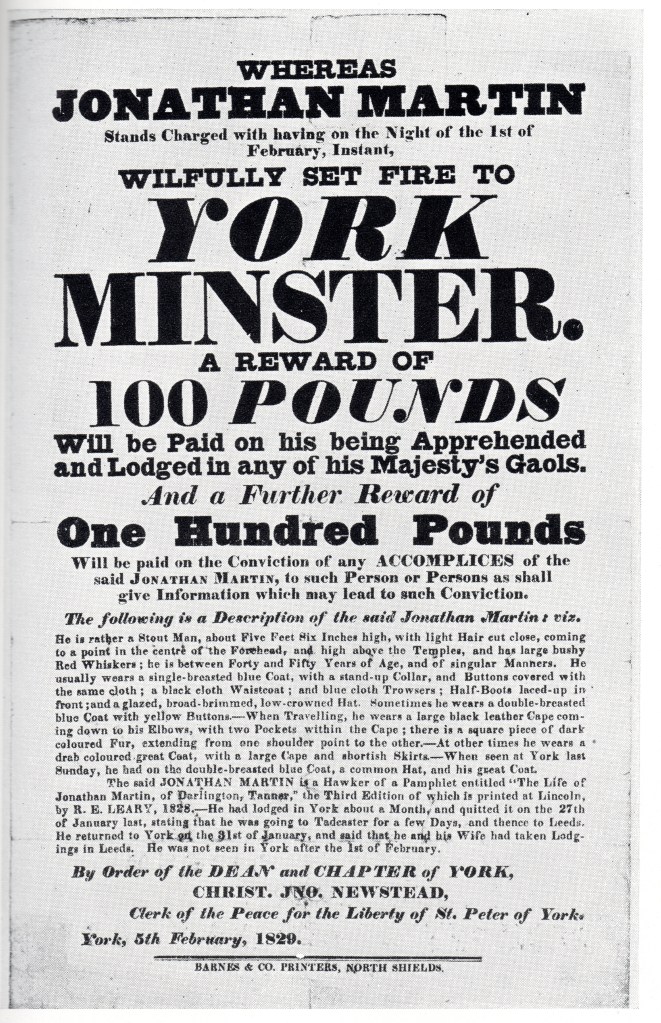

Poster, 5 February 1829, printed by Barnes and Co., Printers, North Shields, reproduced in Balston

Poster, 7 February 1829, printed by H. Bellerby, Gazette Office, York, reproduced in Balston

The Minster in Ruins after the Fire, 1829